Ex-Combatants Association in Great Britain 1946-2003

The Polish Ex-Combatants Association in Great Britain 1946-2003

It may come as no small surprise that following The Royal British Legion the largest army veterans’ organization in the United Kingdom is the Polish Ex-Combatants Association. Formed in 1946 it celebrated it’s half century seven years ago and despite the natural erosion of its numbers as the years pass, is still the most formidable of the organizations of the Polish community in this country.

We remember and remind you”. The partition of Poland following the German invasion on 1.9.1939 and the Soviet invasion on 17.9.39 (design by M. Jarkowski).

To have some understanding of why such an organization came to be in Britain it is necessary to return to the events of the Second World War, the context in which the Association has its basis. On 1st September 1939 Germany invaded Poland, then allied with France and Britain. Poland’s lead in putting a stop to the fateful policy of appeasement, which allowed Germany to occupy other countries on the European continent without firing a shot, began the process of ending German hegemony in Europe. Despite her alliances with the western democracies Poland was militarily left to her fate in September 1939. Declaration of war on 3rd September by Britain and France did not bring the expected relief on the eastern front. On 17th September the USSR invaded Poland from the east. The Polish Campaign came to an end on 5th October 1939 but not before the Polish Government had been reconstituted in France and part of the army managed to cross over to Romania and Hungary from where soldiers escaped to Syria and France. There the Polish Army was reformed to take part in the defense of Norway and then France in May – June 1940. The Polish Air Force also reformed participated in the defense of French skies, whilst vessels of the Polish Navy were operating alongside the Royal Navy from the beginning of September 1939. Following the defeat of France, the Polish Government was evacuated to Britain where it established itself in London. Remnants of the reformed army were also evacuated to Scotland (where for the second time it arose like a phoenix). Its units were formed into the I Polish Army Corps, taking part in the defense of the Scottish eastern coast from the expected invasion. Whilst the army was undergoing reorganization, expansion and training, Polish airmen were playing an important role in the Battle of Britain. Apart from the British, the Polish contingent was the single largest allied contribution to this crucial battle. In all 145 Polish pilots shot down 130 of 1733 German aircraft destroyed during the battle, i.e. 7.5 % of the total. Throughout the war the Polish Air Force which formed four bomber, ten fighter squadrons and one artillery observation squadron, destroyed over 1000 enemy aircraft, 190 V-1 flying bombs, dropped 14,708 tons of bombs and mines and delivered 12,084 aircraft.

A special unit delivered supplies to the resistance armies in occupied Europe. Out of a total of 2,747 such operations 440 were over Poland. The Polish Navy during the war consisted of 2 cruises, 10 destroyers, 1 minelayer, 6-mine sweepers, 2 gun boats, 8 submarines and 10 MGB’s. It took part in many of the crucial naval operations including the evacuation from France in 1940, sinking of the Bismarck, the Battle of the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and Arctic convoys, the Dieppe raid, Operation “Torch” (landings in North Africa), Operation “Neptune” (D-Day landings). In all the Polish Navy covered 1,213,000 sea miles, helped cover 787 convoys, carried out 1,162 patrols and operations sinking same 100,000 tons of enemy shipping. The Polish Merchant Navy consisting in all of 54 vessels, displacing 187,593 BRT tons helped to keep the life lines open, carrying some 4.8 million tons of supplies for the Allied cause.

The Polish Army participated in all the major European operations. The Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade Group took part in the defense of Tobruk (August – December 1941) and the subsequent battle of Gazala. Meanwhile following the Polish – Soviet Agreement of 30th July 1941 and the restoration of diplomatic relations, a new Polish Army was formed in the USSR out of the hundreds of thousands of prisoners taken in 1939 and deportees taken to labour camps and exile in Siberia and other regions of the vast Soviet Empire. Of over a million and a half Poles deported, only 114,000 were allowed to leave the USSR in 1942 to Persia. Of these 70,000 were military personnel, the remainder being civilians, including the elderly, women and children. It was but a small percentage of those left in the wastes of the USSR where many had already died and many more were to die.

Following the link up of the Polish Army in the USSR and the Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade in the Middle East a new Polish Army in the East was formed whose operational part was named 2nd Corps. This force of two divisions and an armored brigade landed in Italy in January 1944 and took part in the subsequent Italian Campaign. Among its achievements was the final capture of Monte Cassino thereby opening the road to Rome (11-18th May 1944) and the taking of the port of Ancona. In the summer of that year it helped to breach the Gothic Line. In April 1945 2nd Corps spearheaded the advance on Bologna, liberating the city on 21st of that month.

On the other side of Europe, the 1st Polish Armored Division landed in France at the beginning of August 1944. Thrown into battle it played a crucial role in the closing of the Falaise Gap at Chambois – Mont Ormel. It went on to liberate tens of villages and towns of Belgium and Holland including Breda. In the spring of 1945 the 1st Armored Division found itself fighting along the Dutch – German frontier along the Kusten Canal advancing into Germany, ending the war with taking the surrender of the Wilhelshaven naval base.

In September 1944 the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Group participated in the bold but disastrous Arnhem drop sustaining heavy losses.

Whilst the Polish Armed Forces in the west took part in nearly all the major operations, in occupied Poland there was formed, arguably the most effective resistance army in occupied Europe. Known as the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) at its peak in the summer of 1944 it had some 250,000 – 300,000 men. It carried out sabotage and diversionary activity aimed at crippling German transport and industrial production. Partisan units in the countryside harried German garrisons making life for the occupying forces as difficult as possible. The gathering of intelligence was deemed a priority. At first there were three occupants: Germany, the USSR and Lithuania (occupying Poland’s North Eastern territories with Wilno at its center). Following the annexation of Lithuania by the USSR in summer 1940 the Wilno district fell under Soviet occupation. The German attack on the USSR meant that from the summer of 1941 to the end of 1943 the whole of Poland was under German occupation. The reversal of fortune and the Soviet advance westwards brought the Red Army onto Polish territory in January 1944. Units of the regional Home Army districts co-operated in the liberation of Poland’s eastern cities and towns only to be later disarmed, arrested, sometimes shot or deported eastwards by the Soviet “liberators”. A new Soviet Communist occupation of Poland was in the making. With the Red Army approaching the Vistula and Warsaw, the Home Army in the capital rose on 1st August 1944 in on attempt to liberate the city from the withdrawing Germans and before the Red Army installed their stooges. A lonely battle ensued against the enemy. With little effective help from her Allies and Soviet indifference (the Red Army stood on the Vistula watching whilst Warsaw bled) the outcome was not in question.

After a 63 day long struggle the Home Army in Warsaw capitulated. The Germans denuded the city of its population and systematically began to raise it to the ground. The city defenders were marched off to POW camps in Germany.

In occupied France the Poles also organized an underground army, which concentrated on gathering industrial intelligence and preparing to attack German garrisons to coincide with the Allied landings.

Throughout the war Polish Military Intelligence was an important contributor to the eventual Allied victory. It began with supplying the British and French with the secrets of the Enigma ciphering machine in July 1939. Polish intelligence supplied the Allies with constant information about German troop movements in the east, arms and industrial production, morale of troops and civilians, theV1 and V2 rockets, and a stream of other information from its intelligence networks in occupied Germany, France, the Balkans, North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula.

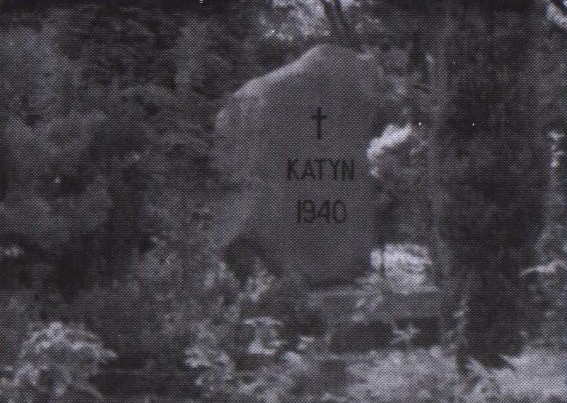

If Poland’s military contribution was out of proportion to her possibilities bearing in mind that the country was occupied, so were her losses. In total some six million citizens lost their lives, the majority in German and Soviet camps. Katyń to this day remains a potent symbol of the crimes of the USSR whilst the countless concentration camps established by the Germans in occupied Poland underline the thinness of the veneer of civilization covering a barbaric people.

Whilst the soldiers, airmen and sailors fought for victory the fate of post war Europe was being settled by the politicians of the big powers. At Teheran and Yalta Poland was shorn of half her territory which was given to the USSR, whilst the remainder of Poland along with the recovered lands in the west, along with the rest of Central and Eastern Europe was given over to Soviet communist occupation. The legitimate rights of the people living in these lands were simply ignored, worse brushed aside.

By the end of the war in May 1945 the Polish Armed Forces in the West, loyal to the legitimate Government resident in London numbered close on 250,000 men and women, including 18,000 Air Force and 4000 Naval personnel. Though some decided to return to Poland, the majority decided to remain in the free world. Of these and the civilians some 150,000 were to settle in Britain. The British Government had to deal with the winding up of the Polish Armed Forces and did this through the institution of the Polish Resettlement Corps from which demobilized soldiers were absorbed into civilian life. The legitimate Polish Government remained in Britain as a symbol of Poland’s determination to regain her independence and rightful place among the democratic nations of Europe.

Polish Ex-Combatants Association representatives at the Field of Remembrance at Westminster Cathedral 8th November 1950.

Though in many aims it was similar to The Royal British Legion it had one overriding goal which clearly distinguished it from The British Legion. The Polish Ex-Combatant Association in GB main aim was to foster among its own community and those of the countries of settlement the idea of an independent and sovereign Poland. Among its political and ideological aims was to defend the good name of Poland and the Poles, and promote co-operation with other Polish organizations. In the field of cultural work the Association placed particular stress on the supporting of Polish Saturday schools and Polish language publications. In the welfare department its main aims were to help: the aged, war invalids, help demobilized soldiers find employment or assist in their efforts to emigrate elsewhere, assist Poles in Poland and elsewhere, help in the redistribution of material aid coming from other sources and finally to maintain care of Polish war memorials and cemeteries. Before the war the Polish community in Britain had numbered not more than a few thousand concentrated mainly in London and Manchester. As has been seen the situation drastically altered after the Second World War making the Poles one of the largest ethnic minorities in Britain. The Association’s peak as far as membership was concerned was in the first years of its existence. In 1947 there were some 257 branches with a total of 30,000 paid up members. This figure dropped sharply over the next two years for reasons outlined later. In 1949 membership fell to about 9000, rising to some 14,500 in 1951 concentrated in 202 branches. By 1956 there were 136 branches with 10,327 members. The late fifties saw a further decline in members, stabilizing at around 6,754 members in 111 branches. Membership of individual branches ranged from 2 to 311 members, though the majority of branches had between 21 and 50 members. Ten years later there were 98 branches with 6,437 members. By 1980 membership had actually risen slightly to just over 7,000 in 103 branches. In 1992 membership remained much the same, though the number of branches fell to 87. One of the features of the last thirty years is the increasing number of women members. In 1945 they formed 14.8% of the total, this figure had risen to 21.5% five years later. In this period the percentage of elderly members grew dramatically, as the chart below indicates.

| 1975 | 1980 |

|

| Under 25s |

3.6% | 2.1% |

| 25-40 years | 8.5% | 6.6% |

| 40-65 years |

59.6% | 48.3% |

| over 65 years | 28.3% | 48.3% |

The fluctuation of membership, especially in the early years was due to the changing structure of the association and the aspirations of the Polish community in Britain.

The history of the Polish Ex-Combatants Association has been subdivided into several distinct periods. The first period 1946-1951 saw the formation of the organization in specific conditions. For most of this period the Polish Armed Forces were still in existence, steadily being demobilized through the Polish Resettlement Corps. The Association’s offices by which it was controlled was the AGM (later this was called every 3 years) which elected a Council from which on Executive Committee was chosen to oversee the day to day running of the organization. The basis of the associations functioning are the local territorial branches. In the first period these coincided with areas where the Polish Army was stationed within the PRC structure. A vast majority of the branches were formed around specific army units (regiments and brigades). In 1947 there were 240 unit branches. Two years later when the PRC was all but wound up only 8 unit branches remained. With the disappearance of the unit branches there was a sharp rise in the number of hostel branches though this too was a passing phase. The hostels housed demobilized soldiers who had found employment either locally or in other areas. In March 1949 there were 122 hostel branches. One of their features was the sharp decline in branch membership. The main reason for this being that they were no longer based on military units with an organized structure.

Membership was totally voluntary. The hostels offered cheap accommodation near local employment. The years 1948-1952 were marked by the importance of the hostel branches. The existence of an organized ex-combatants association allowed for the exertion of influence on the hostel authorities to improve conditions. Often, once one SPK branch showed its organizational ability and power it found support among the various other nationalities living in the hostel.

The negative aspect of the hostels was that they formed individual small ghettos. The liquidation of the Polish Armed Forces completed by 1949 posed a major challenge to the SPK central authorities: how to reach the vast number of veterans, as contact which had been simple with the existence of an army structure was often lost following demobilization. To help overcome organizational difficulties, an intermediary level was created between the branches and central authorities in London. Eventually six SPK districts were set up. It was essential to reach the hostels and in this the British authorities assisted in locating the hostels and supported the establishment of SPK branches there. From the point of view of the SPK central authorities this was of crucial importance. This was a time of momentous changes. The tragic end of the war had left many soldiers demoralized, homesick, and unable to return to their native land. There was a crisis in confidence in their leaders and the vast majority of ex-soldiers wanted to establish a new life, better themselves and set up families. Many just wanted to blend into British life, forsaking their Polish roots. Apathy was the main enemy. This explains the sharp decline in membership by 1950. The central authorities placed great importance on the need for the local branches to have their own veterans clubs where they could meet together, an opportunity to strengthen social life in a Polish atmosphere. Initially it was planned that one such club should exist in each of the six districts: Glasgow, Manchester, Sheffield, Bedford and Bristol. In London the SPK headquarters at 16 – 20 Queens Gate Terrace played this role.

The phase of hostel branches was short lived and by 1950 their number began to drop dramatically as individual soldiers and their families began to find permanent homes, either renting or purchasing flats or houses. In 1949 dead branches were struck of the central register of branches and new ones were only set up in towns or hostels where the chances for their organizational growth was sound. The number of town branches steadily rose. The districts having served their purpose in helping to organize local branches began to be dissolved in 1951. Moreover the cost of keeping on this intermediary structure was proving prohibitive. By the early 1950s another important factor in the long – term existence of the SPK became clear. Polish veterans and their families were reluctantly getting used to the idea that life in exile in the UK may be of some considerable duration. An early return to a free Poland was not on the cards.

General W. Anders opens the XV Meeting of the Polish Ex-Combatants Association, July 1961.

Though careful to avoid becoming a political organization the SPK’s central ideological aim was to “keep faith with the national ideals in our service for society with the same conscientiousness that we kept faith in the ranks of the Polish Armed Forces”.

During the 1950s as membership declined the more active branches were designated regional branches whose task was to help the weaker, less active branches and more importantly prepare new active volunteers. By 1956 73% of branches were city/town branches in areas which had a large Polish population working in the local industries. In 1956 there were only 4 hostel branches left. The sharpest decline occurred in the late fifties, following a brief liberalization by the communist regime in Warsaw, resulting in mass reunion of families and ever increasing number of visits to Poland. Moreover as the ex-soldiers more and more often had full time stable jobs, many turning to professional occupations there was less time for social activity. The 1960s saw a further fall in the number of branches but at the same time a stabilization in the number of members. More importantly for the future this decade was a period of economic consolidation for the branches though at the cost of greater social welfare aid for individual members. Also the number of second generation Poles (i.e. those born in exile in the UK) who were becoming more active within the SPK rose. This was especially true of the provinces where the SPK clubs were often the only focal point for Polish community life. In 1965 both the Bradford and Blackburn branches had over 50% of members who had been too young to serve in the Polish Armed Forces.

The 1970’s saw the move of SPK HQ from Queens Gate Terrace to the newly built Polish Social and Cultural Center in Hammersmith. Meanwhile the role of the provinces was enhanced through the introduction in the late sixties of a new tier in the organizational structure – namely regions. These facilitated the co-ordination of work allowing for regional conferences with emphasis on the problems of a given region. The regions whilst maintaining the central ideological position were given greater autonomy. The membership rose slightly during the 1970’s. In 1971 there were 3 hostel or settlement branches with 188 members and 96 town branches with 6,325 members. A decade later there were 4 hostel or settlement branches with 124 members and 99 town branches with nearly 7000 members. A constant problem for both the central authorities and the local branches was attracting new membership especially among the young second generation Poles. The end of the 1980’s saw fundamental changes occurring in Poland culminating in the regaining by Poland of its independence and throwing off the Soviet Communist yoke. Independence day, 22 December 1990, brought to a close a major chapter in Polish post war history and that of the exiled community. The official state structures in exile began to wind up their activities. The central tenet of the SPK’s aims had been more or less achieved. The 1990s began a period of re-adjustment to the new realities. Normal regular contacts with Poland and its official institutions and veterans organizations began to be the norm.

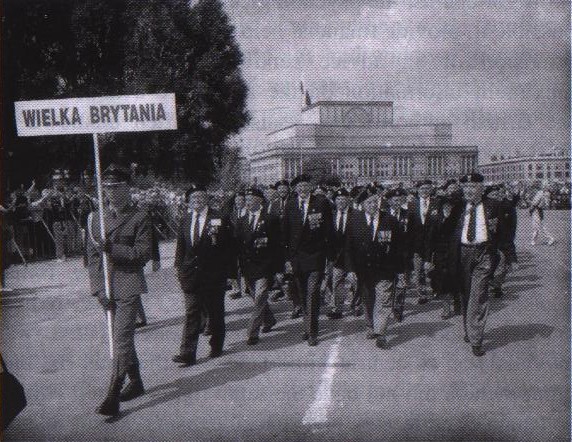

The delegation of the Ex-Combatants Association in Great Britain marching in Warsaw, the capital of a free and independent Poland, August 1992.

Apart from the central aim of regaining Poland’s independence the SPK’s main role was to bring assistance and help to Polish war veterans within the limited means available to them. The finances for this were found through various work schemes of the central authorities and the profits made by the local branches. This came from membership subscriptions, activities of the SPK clubs, houses, farms and workshops. Apart from the financial profit these activities provided employment for several hundred ex-soldiers. Of special importance was the need to take care of the elderly, invalids and sick – to fight against the psychological stress and in so far as possible to provide financial help for the most needy. The provision of an advice center which could provide maximum information on the assistance available from the British authorities-assistance often unknown to exist, due partly to the language barriers, partly due to pride not to take charity. The main avenues of this help lay in the legal field, employment matters and emigration. The SPK helped in the setting up of workshops and small businesses by providing initial loans (not exceeding £ 120). This helped reduce unemployment among ex-soldiers. Care of the war invalids was of central importance, as this was the one group, which did not have the same rights as their British colleagues and received no special pension. Financial and material help to ex-servicemen’s families in Poland was another important role of the SPK. It should be recalled that the communist regime denied any assistance to the families of Polish soldiers who fought in the Polish Armed Forces in the West. The SPK intervened with the British government to facilitate the reunion of families. This was of special note in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. Many matters of advice were dealt with by the SPK Bureau of Information and Advice set up in 1947. At one time it employed 15 persons dealing with up to a couple of thousand enquiries weekly. During the year 1950/1951 some 750 ex-servicemen received one off grants, loans, parcels for the sick and 420 loans for those setting up small businesses. This was done in conjunction with the Polish Soldiers Assistance Fund. In 1956 The Polish Trustee Association Ltd. was set up to administer the carrying out of wills of ex-soldiers with families in Poland and sending of old age and widows’ pensions to Poland. The problem of veterans reaching retiring age increased greatly during the 1960s. The SPK worked especially closely with Polish “villages” such as Penrhos and Stover Park, helped in the upkeep of No. 3 Polish Hospital in Penley in north Wales, the last of the Polish military hospitals remaining from the war.

Since December 1962 the British Government has been providing an annual grant for the needs of Polish ex-combatants who had served “under British operational command and are living in the UK in distress”. Between 1963 and 1973 the SPK assisted in distributing £ 845,000 received form the British Government. In 1979 some 3000 veterans were receiving help, half of them on a regular basis.

After the crushing of the Solidarity Movement and the introduction of martial law in Poland in December 1981 the SPK joined in the massive assistance being provided to Poland in the form of food and clothes parcels, medical aid, by various Polish and British charity organizations in Britain. As an example the Bradford SPK branch sent some 40 tons in food and clothing and £ 2000 in cash to Poland between 1981 and 1989. On the branch’s initiative A public collection raised £ 5000 on the streets of Bradford, which was donated to Medical Aid for Poland. This type of fund-raising and assistance was multiplied by the other SPK branches.

In 1990 the SPK donated £ 200,000 to the Help for Poland Fund earmarked for sick children. Not only was financial assistance received from the British Government from 1963 onwards. The Royal British Legion also provided resources for distribution among Polish veterans living in Poland. In December 1984 it gave £ 3000 of such aid (sent in the form of $ 15 bonds). Meanwhile the annual British Government grant rose to £ 360,000 in 1995, though it was not until very recently that the long battle to obtain permanent war invalid pensions for Polish ex-servicemen was won.

From the very outset the SPK in Great Britain regarded as one of its main missions the necessity to look after the cultural needs of its members and more importantly the nurturing and preservation of the Polish identity of the children of ex-servicemen born in exile. This explains the extent to which SPK branches went to establish local Polish libraries, music, folk dancing and theatrical ensembles. In 1950 there were 200 libraries with some 50,000 volumes. The majority of patriotic and national anniversaries were often organized by or with the assistance of the local SPK branches. In this period there were some 25 choirs, 20 – 30 orchestras / music ensembles and 6 theatrical troupes. Tours around Polish centers were organized. Foremost in the mind of SPK leaders (as with all other exiled organizations) was to preserve Polish culture and customs. Thus the emphasis on the need to read Polish books, to organize Polish film shows. These were primarily pre war films as the films made in communist Poland often contained blatant Soviet propaganda.

The SPK’s venture into its own publications had mixed results, though there were certain exceptions such as “To i owo” (This and that) published by Branch no. 451 in Bradford or “Kombatant” (Combatant) published by Branch no. 415 in Chesterfield. With the passage of time more information appeared in the local British press as relations between Polish and the English, Scottish and Welsh communities grew ever more closer. Local branches were trying to keep the British press informed about Polish affairs. The central SPK authorities in London took over one of the Polish bookshops and ran it until the 1990’s. They also had their own publishing house “Gryf”. For some twenty years from 1964 the SPK took over the publishing of the monthly “Orzeł Biały” (White Eagle) which contained historical and political articles, expounding the creed of Poles in exile.

As already mentioned the SPK was very active in supporting Polish Saturday schools. In 1956 there were 60 such schools with 2,200 pupils and 140 teachers either directly run by local SPK branches or in conjunction with other organizations. A network of school inspectors was set up and the SPK helped to provide the necessary finances for the schools. With the passage of time the role of Polish parishes in running the schools increased. In 1969/1970 39 schools with 2,200 pupils and 170 teachers were run solely or jointly by the SPK. In 1990 36 out of 75 schools were run by the SPK. One of the problems of which special care was taken, were the efforts of the communist regime to infiltrate and influence the schoolchildren. Unsolicited pro-communist and atheistic literature was often sent. The school authorities had to be on their guard all the time against these efforts at corrupting Polish youth in exile.

Junior classes of the Polish Saturday School in Manchester run by Ex-Combatants Branch no. 181.

The 1970’s were a period of increased cultural work. The number of local libraries had fallen to some 30 with 30 – 35,000 volumes. The most vibrant branch libraries were at Manchester, Sheffield and Penrhos. At the beginning of the decade there were some 10 theatrical troupes, which gave over 50 performances during the 1970/1971 season. During that same year 12 SPK dance groups gave some 100 performances, 12 choirs gave 110 performances and 3 music ensembles over 50 performances. In as much as was within their possibility the SPK gave material support to the two Polish secondary boarding schools: Pittsford for Girls, and Fawley Court for Boys. An important way to involve the young in Polish life was through sport activities. On this the SPK laid much emphasis. In any case following the war many of the ex-servicemen were young and fit, and this was an ideal way of maintaining a cohesive Polish life outside of work. Thus the SPK spearheaded the setting up of sports clubs. By spring 1950 there were 44 sports clubs attached to local branches. Many were initially fitted out with sports equipment from the demobilized army clubs. Once the clubs were established and running the central SPK authorities organized various national competitions. On the initiative of the SPK in GB, the Association of Polish Sports Clubs was created in 1953 as a central organizing sports body. Among the most prestigious national competitions was the General Anders Football Trophy. In the 1953 finals 27 teams participated where “Silesia” beat “Junak” 4:2. The annual event took place at Cannock. In all 76 games were played by 500 players with 22,000 supporters watching the matches. In 1970 there were 52 sports clubs. At this time 15% of the SPK in GB headquarters’ budget was spent on sport (some £ 1,200). Apart from the purely sporting aspect this was another method of fostering Polishness.

In 1975 a new trophy was instituted, the Gen. Karol Ziemski Trophy, awarded to the team which spoke the best Polish. For several years running the “Polonia” team from Bradford won the prestigious award. In 1989 there were 45 sports clubs including approximately 20 football teams, 5 netball teams and 12 ping-pong teams.

The Ex-Combatants “Polonia” Sports Youth Club from Bradford which won the Gen. Anders Football Trophy three years running 1968-1970.

Though the SPK was not a political organization and underlined this regularly, it did have as one of its aims a political goal – namely the regaining of Poland’s independence, and informing the British public about Poland. Events in communist Poland were followed closely being a topic of discussion at every AGN. Throughout the early post war years, several manifestations were organized culminating in a number of protest actions reminding the British public of the plight of Poles in the USSR, urging the British government to help pressure the Soviet government to allow them to leave the USSR and return to Poland. The SPK played a conspicuous role in supporting the “Common Cause” a British initiative collecting signatures for a petition against a visit by Bulganin and Khrushchev to Britain in the spring of 1956. When this failed the SPK were at the forefront of the organizers of a protest march through central London on 22 April 1956. Over 20,000 Poles marched silently through London bearing banners and culminating in the handing of a petition to Prime Minister Anthony Eden demanding that he raise the following in talks with the Soviet leaders: free elections in Poland, freeing of Poles held in Soviet labour camps, revealing the truth about the Katyń Massacre. The following day the Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd saw Polish leaders in exile and the Polish memorandum was the subject of discussion in the House of Commons.

20,000 Poles march silently through the streets of London in protest at the visit of Soviet leaders Bulganin and Khrushchev, 22nd April 1956.

On the question of Poland’s frontiers the SPK stood firm on the eastern frontier agreed to at the Treaty of Riga in 1921 and in the west on the river Oder – Neisse. The SPK central leadership and local branches constantly passed resolutions supporting the opposition in Poland in its attempts to force change. They protested at all signs of crackdowns and state sponsored terror introduced by the communist regime in their bid to hold on to power. There was little practical help in this direction, which the SPK could give. On the other hand it could and did do everything to make the local populations aware of Poland’s plight. In 1966 Poland celebrated 1000 years of Christianity. The SPK was at the forefront of organizing a variety of celebrations. By far the largest, was the one at White City Stadium, which drew over 20,000 people. The 1970’s saw a growing involvement in a number of initiatives aimed at erecting memorials to the 14,000 Polish officers, professionals and intellectuals murdered by the Soviets at Katyń, Charkov and Miednoye. The unveiling of the central Katyń memorial at Gunnersbury Cemetery in London became a great patriotic manifestation.

The Katyń Memorial in Gunnersbury Cemetery commemorating 14,000 Polish regular and reserve officers murdered by the Soviets in spring 1940.

Local SPK branches led initiatives to erect Katyń memorials as well as other Polish memorials in their towns, such as in Wrexham and Perth, commemorating Polish soldiers, sailors and airmen who died in exile on the road to a free Poland.

The unveiling of the Polish memorial in Wrexham Cemetery erected on the initiation of the local Ex-Combatants Association Branch, 1st October 1989.

The Katyń Memorial in the grounds of the club house of Branch no. 50 in Kirkcaldy.

During the 1980s the SPK was active in care support for Polish students in the UK following the crushing of the Solidarity Movement. Despite martial law this was a period when increasing practical help could be afforded to Poland directly and the SPK membership was very active in organizing and providing material aid.

An integral part of keeping the flame of Polish freedom alive in exile was the struggle to maintain Polishness in the new generations, the sons and daughters of servicemen and servicewomen. Thus, much attention was paid in supporting various youth activities from Saturday Polish language schools, through the Polish Scouting Movement in Exile and youth clubs. Encouraging the post war generation to become actively involved in the SPK as members proved more difficult and its success was limited, being most effective in the provinces rather than in London.

The regaining by Poland of independence in December 1990 and the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, the disintegration of the Soviet Empire and regaining of independence by the nations of the USSR and transformation of the Russian SSR into Russia opened up new avenues of activity for the SPK in Great Britain as well as for the World Wide SPK Federation. A lot of energy and help began and continues to be channeled in helping Poles in Kazachstan and other far corners of the old Soviet Empire. The process of erecting, often re-erecting Polish memorials and cemeteries commemorating those who were deported by the NKWD and died in the USSRs eastern republics in labour camps, exile or those lucky enough to reach the Polish Army in 1941/1942 but who died before they were evacuated to Persia.

In 1995-1996 the SPK in Great Britain celebrated the 50th anniversary of the end of the war and its own golden jubilee. Various initiatives to commemorate this event were set up. By far the most important was the one to make a central register of all Polish graves in the United Kingdom. An English language pamphlet “Poland’s contribution to the Allied Victory in the Second World War” was commissioned from the author of this pamphlet. It was subsequently sent to all MPs and other British bodies. It led to the Prince of Wales inviting a delegation of 80 SPK members to Highgrove. A detailed history of the SPK in GB was commissioned in Polish from T. Kondracki a Warsaw historian.

An 80 strong delegation of Polish Ex-Combatants, invited by HRH The Prince of Wales to Highgrove 1996.

An integral part of the activities of the SPK in Great Britain are the club houses. Where possible local branches purchased or leased premises, which often became a focal point for Polish life, not just as a meeting for social occasions but also a place where Polish language schools could have their classes, meeting place for other Polish organizations. Preserving their Polish character the club houses often became a venue for various functions of the local British community, fostering ever-closer relations and co-operation between the differing ethnic minorities and the local British population. In some cases local British and other minority organizations have their offices in the Polish SPK club houses.

The club house of Branch no. 274 in Peterborough.

In all, 38 club houses were purchased between 1947 and 1982 at a total cost of Ł 447,073. Of these 26 were still active in 1996 the remainder having been sold as the local branches dwindled.

The over half a century long activities and successes of the SPK in Great Britain in such a wide field of varying enterprises were and are possible, only thanks to the hundreds of active volunteer members who run the whole organization especially at branch level. The unswerving loyalty and support of the corps several thousand members provide the basis for the wider activities of the SPK. The sacrifice of all these people giving their time, work and more often than not financial support has been instrumental, in providing and fostering a separate organized Polish social life for tens of thousands of Poles far from their homeland. In more ways than one it is a unique achievement.

The emblem of the Polish Ex-Combatants Association and decorations and badges for exceptional service to the Polish cause awarded by the Association to its members and others.

Following the war, some 1200 demobilized Polish soldiers and their families settled in Sheffield in 1947. A further 300 persons came from the displaced camps in Germany (poles who had been taken to Germany as slave labor). In February 1948, a new SPK Branch, No. 439 was formed by amalgamating two previous branches. In the first instance a library was organized for the needs of the Polish community and in 1948 a sports club for the young was set up. During the 1950s the Sheffield SPK Branch no. 439 with the help of the central authorities in London purchased a house for use as a social club drawing together members and guests. In 1955 there was a paid up membership of 170 persons. The Branch organized its own music ensemble which gave concerts and played at various functions organized by the branch. It also had its own theatre troupe. From its very inception the branch was very active in helping to organize and finance the local Polish Saturday morning school where Polish children learnt to read and write in Polish as well as learning about Poland’s history and geography. In tandem with the educational needs of second generation Polish children the branch took care of the local Polish scout group made up of the school children.

Membership of Branch no 439 rose steadily reaching 200 in 1956, 290 in 1980 and 315 in 1995, making it at that time the third largest branch in the UK. The Sheffield branch being one of the more dynamic branches helped the weaker ones in its vicinity. Various fund raising projects and street collections were organized for Polish charitable its vicinity. Various fund raising projects and street collections were organized for Polish charitable causes.

The Branch helped the Polish Scouts Movement in Exile to purchase a permanent center at Fenton on the river Trent.Following the introduction of martial law in Poland in 1982 the Sheffield SPK branch sent some 60-tons of parcels worth over £20,000.

SPK Branches in 2000

| i) | Figures in brackets denote number of member in 1995 |

| ii) | ”CH” denotes branches which had/have their own club-home |

| REGION 1 | |

| Branch No. 179 | Blackpool (22) |

| Branch No. 180 | Preston (90) (CH) |

| Branch No. 183 | Blackburn (132) (CH) |

| Branch No. 251 | Chorley (52) (CH) |

| Branch No. 268 | Liverpool (21) |

| Branch No. 488 | Lancaster (48) |

| REGION 2 | |

| Branch No. 413 | Leeds (110) |

| Branch No. 416 | Keighley (46) |

| Branch No. 417 | Halifax (41) (CH) |

| Branch No. 440 | Huddersfield (102) (CH) |

| Branch No. 451 | Bradford (300) (CH) |

| REGION 3 | |

| Branch No. 181 | ”General Sosnkowski” – Manchester (350) (CH) |

| Branch No. 189 | Todmorden (10) (CH) |

| Branch No. 201 | Northwich (26) |

| Branch No. 220 | Penrhos (48) |

| Branch No. 231 | Ashton – under – Lyne (18) |

| Branch No. 232 | Oldham (52) (CH) |

| Branch No. 240 | Rochdale (37) (CH) |

| Branch No. 246 | „General Sulik” – Bury (appx. 30) |

| Branch No. 270 | Merseyside (65) |

| Branch No. 469 | Wrexham – Penley (55) |

| Branch No. 479 | Crewe (38) |

| REGION 4 | |

| Branch No. 415 | Chesterfield (40) (CH) |

| Branch No. 418 | Lincoln (77) (CH) |

| Branch No. 439 | Sheffield (315) (CH) |

| Branch No. 441 | Doncaster (35) |

| Branch No. 445 | Rotherham (27) |

| Branch No. 499 | Scunthorpe (81) (CH) |

| REGION 5 | |

| Branch No. 382 | Loughborough (44) |

| Branch No. 407 | Mansfield (70) (CH) |

| Branch No. 431 | Leicester (116) (CH) |

| Branch No. 432 | Derby (140) |

| Branch No. 465 | Nottingham (105) |

| REGION 6 | |

| Branch No. 182 | Telford (35) |

| Branch No. 215 | “Pomiarowiec” (Field Surveyor)– Kidderminster (97) (CH) |

| Branch No. 225 | Birmingham (180) |

| Branch No. 236 | “Kolejarz” (Railwayman) – Worcester (64) (CH) |

| Branch No. 239 | Wolverhampton (101) |

| Branch No. 242 | Stafford (72) |

| Branch No. 252 | Stoke – on – Trent (60) |

| Branch No. 301 | Rugby (56) (CH) |

| Branch No. 399 | Coventry (58) (CH) |

| REGION 8 | |

| Branch No. 108 | Ipswich (53) |

| Branch No. 274 | Peterborough (120) (CH) |

| Branch No. 293 | Wellingborough (32) (CH) |

| Branch No. 296 | Cambridge (56) |

| Branch No. 302 | Bedford (63) |

| Branch No. 319 | Witham (22) |

| Branch No. 364 | Luton (335) (CH) |

| REGION 9 | |

| Branch No. 340 | Cheltenham (50) |

| Branch No. 342 | Bristol (158) (CH) |

| Branch No. 365 | “Kresy” (Borders) – Bridgwater (18) (CH) |

| Branch No. 378 | Dursley (27) |

| Branch No. 380 | Trowbridge (68) |

| Branch No. 475 | Cardiff (67) |

| REGION 10 | |

| Branch No. 115 | Amersham (78) (CH) |

| Branch No. 192 | Slough (111) |

| Branch No. 200 | Aylesbury (22) |

| Branch No. 286 | High Wycombe (71) |

| Branch No.334 | Swindon (204) (CH) |

| Branch No. 344 | Oxford (71) (CH) |

| Branch No. 386 | Reading (94) |

| REGION 11 | |

| Branch No. 25 | Edinburgh (117) (CH) |

| Branch No. 27 | Aberdeen (34) |

| Branch No. 28 | Perth (52) (CH) |

| Branch No. 36 | Falkirk (168) (CH) |

| Branch No. 50 | “General Maczek” – Kirkcaldy (200) (CH) |

| Branch No. 60 | Dundee (50) (CH) |

| Branch No. 105 | “General Maczek” – Glasgow (148) (CH) |

| REGION 12 | |

| Branch No. 4 | London – Ealing (93) |

| Branch No. 11 | London “Środkowy Wschód” (Middle East) (136) |

| Branch No. 30 | “Żandarm” (Provost) – London (45) |

| Branch No. 106 | Godalming-Horsham (56) |

| Branch No. 112 | London – Enfield (33) |

| Branch No. 113 | “Spadochroniarz” (Paratrooper) and 1st Armoured Division (122) |

| Branch No. 114 | “Harcerz” (Scout) – London (25) |

| Branch No. 118 | Brighton – Hove (54) |

| Branch No. 123 | London – South (199) |

| Branch No. 309 | Southampton (50) |

| Branch No. 316 | London (mainly veterans of the 316th Women’s Transport Company ) (40) |

by

Andrzej Suchcitz

London – 2003

© The Polish Ex-Combatants Association

in Great Britain and Andrzej Suchcitz – 2003

THE POLISH EX-COMBATANTS ASSOCIATION

IN GREAT BRITAIN

240 KING STREET – LONDON W6 0RF

Printed by Polprint